Over the past year, long debates on the issue of reserving land in prime areas for public housing has highlighted the pros and cons of doing so. While it may serve to have greater inclusion between income groups in central areas and promote diversity, it also brings about the “lottery effect”. From the case of Pinnacle@Duxton, it is apparent that successful bidders of Build-To-Order (BTO) flats have enjoyed excessive windfall gains when selling their apartments in prime areas like Tanjong Pagar. Given Housing Development Board (HDB)’s balloting system, many have found this unfair for BTO buyers in other parts of Singapore.

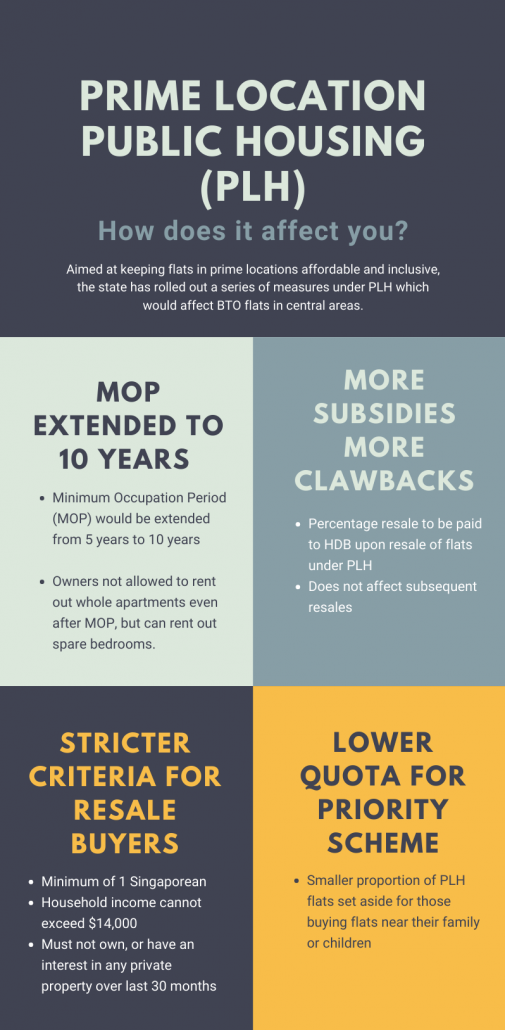

In hopes of balancing out such inequality while maintaining the perks of having public housing on prime land, the state has announced a series of measures. The first project to be affected by PLH includes BTOs which would be launched in Rochor estate this November. Given the scale of the schemes, you might be wondering how PLH could affect you and your future BTO purchases. This article uncovers the measures of PLH and how it would affect the future of HDB purchases in prime areas.

1. 10-year MOP

Minimum Occupation Period (MOP) is the required minimum period of stay in Built-To-Order (BTO) flats. Typically 5 years, MOP is meant to prevent buyers from flipping houses and reselling shortly after receiving their subsidized BTO flat, as that would defeat the purpose of promoting homeownership through these schemes.

With the implementation of a 10-year MOP which is double the time, this is likely to bring about longer waiting times – a 15 to 16 year long wait from successfully bidding the BTO until being allowed to resell the flat. Moreover, owners would not be allowed to rent out their apartments even after MOP although renting of spare rooms is permitted.

2. More Subsidies, More Clawbacks

Since the apartments in central areas command higher market values, additional subsidies on top of existing subsidies will be offered to buyers to ensure that these flats are accessible to all. However, this also means that buyers are expected to return a percentage of the flat’s resale price to HDB when the time to sell the flat comes. This measure seeks to address one of the main issues highlighted in the debate – the “lottery effect”. Simply put, the inequitable gains from securing a HDB flat in prime areas has magnified the random effect of balloting. With subsidy clawbacks in place, the system would be fairer as those residing in public housing at premium locations do not get to earn “excessive windfall gains” upon resale of the apartment. It would also be more equitable to BTO buyers in other parts of the city.

One potential issue would be sellers pricing in the subsidy into the selling price to recover their “losses”, which might result in higher resale prices. This might be counterintuitive to the state’s efforts, but the Ministry of National Development (MND) has stated that this is likely to be left to market forces for the time being as measures have already been put in place. Aside from the typical market forces of supply and demand, the state has ringfenced the pool of eligible buyers and lengthened the MOP. Further interference of such may distort markets.

3. Stricter criteria to purchase resale flats

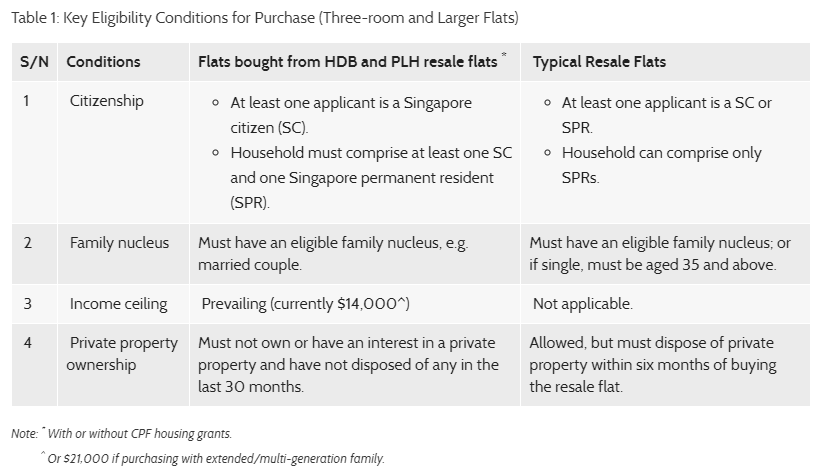

Typical resale flats allow for minimally one applicant who is a Singaporean Citizen (SC) or Permanent Resident (PR). Under PLH, there will be a smaller pool of resale buyers as at least one buyer must be a Singaporean Citizen. Additionally, there is an income ceiling of $14,000 imposed, a stark contrast to the current resale market that has no cap. Singles are also not allowed to buy resale HDB flats under PLH.

These measures seek to reduce the potential windfall gains from buyers. Although making up a mere 0.3% of the market, there has been a rise of HDB flats transacting at over $1 million dollars in recent years especially in the city center. By limiting the pool of resale buyers, this would help to ensure affordability and allow equal access to prime housing. At the same time, this curbs the prices of the apartments from skyrocketing with the private market.

4. Lower quota for priority scheme

While the requirements to purchase the BTO flats in prime areas is similar to buying BTO in any other area, it would have a lower quota for priority allocation under the Married Child Priority scheme. This scheme is for those who wish to live with or near their parents or children and sets aside up to 30% of BTO units. This could help to mitigate the “lottery effect” as those with families living in prime areas have less advantage in the balloting system.

Implications for the future

Another implication could be a rise in prices of housing in the perimeter of prime areas. This could mean that the flats on one side of the road could be labelled as “prime area” and restricted by PLH, while HDB flats on the other side are not. Thus, until the state expands the boundary of central areas, buyers may turn to alternatives such as public housing that are unrestricted by PLH.

Amid lower demand and longer waiting periods, pioneers under PLH should be ready for longer transaction times when it comes to selling their flats. The measures that have been rolled out by the government have its pros and cons and it is advisable for potential buyers to take a deeper dive into the considerations of purchasing a HDB under the PLH to ensure that it is aligned with their goals for the future, before making a commitment to purchase.

Want to find the best mortgage rate in town? Check out our free comparison service to learn more!

Read more of our posts below!